ON the jacket of the book in front of me there is a colour

photograph of a climber swathed in awkward bundles of climbing rope, one hand

on an ice axe plunged into dangerous-looking powder snow,the other clutching a

short second axe. From the body rope hang ice-screws and pitons, and the straps

on the boots show he is wearing crampons. The strong face beneath the shock of

snow-rimed hair is not smiling. The mouth is open in an interrogatory glance, elongating

the lines on the cheeks almost to lantern jaws. The man is Tom Patey, who crashed to his death on May 25, 1970.

One Man’s Mountains is a collection of his best essays and verses, and they

catch the spirit of the ’50’s and ’60’s as surely as Alastair Borthwick caught

the 30’s in his classic Always a Little Further.

I discussed this book with Tom when We climbed the Cioch

Nose in Applecross together only a few days before he parted from his rope

while abseiling from a sea stack called The Maiden at Whiten Head, on the

remote north coast. The day Tom died he was due to meet Olivia Gollanz,

publisher of his book. They were going to discuss his work and he intended to

resist any rewriting of it, “ Because I’ve worked damned hard on these pieces,

and I need the money now.” Tom, the unashamed television climber, willing to

take part in any B.B.C. circus for the fun as much as the reward, wrote the

best of his work for sheer pleasure. And when he did write for money it was

often to satirize “The Professionals.”

The book shows the evolution of a climber from days of innocence when he

was a shy and retiring schoolboy, to his extrovert singing and piano accordion

playing on Aberdeen Climbing Club meets, when the bar-room jollity was as

important as the climbing. His chapter, “Cairngorm Commentary” catches the

spirit of these times, and is, I think, one of the best pieces ever written on

young men and mountains.

In it he describes his epic snow and ice ascent of the

Douglas Gully on Lochnagar that I first climbed with Brooker, Smith, Taylor and

Patey. It was November, cold, wet, and we went to Eagle Ridge of Lochnagar.

Adam Watson was there, too, and we formed two ropes-Patey leading one and

Brooker the other; It was my introduction to rock climbing on the mountain, so

they had chosen the narrowest and steepest of the ridges. It was a test of

adhesion to hard, slippery rock with hands half frozen by falling sleet, but

Tom was exuberant as he scraped, lunged and grunted, drawing breath only to

extol some feature of the elegant route that I might be missing. By contrast

Taylor looked meticulously controlled and demanded his right to lead some of

the choicer pitches.

Tom put our ascent to good use, by doing the climb again the

following Week-end when it was submerged

in eight inches of powder snow. His

companion was Tom Bourdillon, who happened to be giving a lecture on Everest in

Aberdeen and found that a by-product of it was to be doing the hardest climb of

his life with the reigning Tiger. I remember on the Bealach nam Bo, as we sat

in the car listening to the rain, asking Torn if he had regrets about being a

doctor when he might have become a professional climber. His reply was

vehement. I’d‘ rather be a good doctor any day. Climbing is not a reason for living.

Providing a good medical service to a remote region like Ullapool and the

North-West is as important to me as any climbing.

I've worked hard to build up that practice, and I’ve enjoyed

it, though I'd like more time for climbing.”

Then he confided to me his remarkable intention to ‘solo the North Face

of the Eiger that August. He reckoned from his past attempts with others that

he needed only one good day to top the greatest mixed route in Europe” His

words. His intention was to prepare the way so as to be able to go up in the

dark when conditions were right, using his exceptional speed to forge up the dangerous

upper part at break of day, before the stonefall barrage could begin.

Why did he want to do a route that had been done over a

hundred times before, when he was such a pioneer of new ways? “ Because it has

every problem in climbing heaped on top of each other. The big objection to it

is the time it takes-so you are liable to be caught out by the weather. Get up

it before the stuff starts to fall and you have only gravity to contend with.

Every day you are up there lessens your chance of staying alive. And I Want to

live.” Six days later, Tom was dead.

Ullapool lost a good doctor, as a great many of the

townsfolk have told me. Winner of the Gold Medal for Physiology in his second

year at university, he could have gone very far in medicine had he given free

reign to his academic abilities. Good G.P. though he was, Patey had in him a

tough, almost a callous streak, a demand that his friends be as hard as he was.

Before he graduated I was due to give a lecture in Aberdeen, but collapsed with

flu on the eve of departure from Glasgow. The doctor was called and pronounced

me unfit to travel. “ Under no circumstances must you go,” he warned.

I phoned Adam Watson with the bad news. He was sympathetic.

Somebody else would have to be found to take my place. An hour later the

ebullient Patey was on the line, assuring me that most doctors were fools, that

a man like myself shouldn’t be stopped by anything so trivial as flu . . .So I

arrived in Aberdeen. Gave my talk, was whisked about from one house to another

afterwards,and finally driven to Ellon in a snowstorm to arrive in the early hours

of the morning at a stone cold house. What Patey did not tell me was that his

parents were away and that the house had been lying empty for the last three weeks.

The bed was like an ice-box.

Yet I enjoyed myself, watching him sit down at the piano the

moment we came into the house and, between songs, hearing him enthuse about

climbs he had done and was going to do. The fact is that Patey had a way of

expanding you with his presence. Our eighteen years of age difference disappeared.

The University Lairig Club flourished then as never before or since. With

upwards of seventy members attending meets, these trips to Lochnagar were

brought down to package-deal terms at 5s a head.

Many came for the jollity, though nearly all enjoyed a

little fresh air prior to the evening’s entertainment. I have never been a

lover of big parties, so I was rather shaken when Tom joined our party one New

Year, with what looked like one of these meets of lads and lasses. And they

brought with them a potent concoction of spirits, and as Tom took liberal swigs

between dance numbers, his agile fingers became livelier and livelier on the

accordion. He was still playing when most of the dancers had collapsed. I don’t

know when he went to bed. But he was with us in the morning for a climb which

he declared to be a new route. True, he looked terrible, pale as a ghost and

racked by a cough. But this was not abnormal. The cough came from smoking, the

face belied a man with so much stamina that frequently ran to the crags,

punched a few hard routes and jogged back again.

There is a question-and-answer song about Tom....How

does he climb, solo and so briskly?.......On twenty fags a day,

and Scotland’s good malt whisky.

Tom’s own satirical songs published in the book are subtly

delightful, especially his 'Alpine Club Song'.

Our climbing leaders

are no fools,

They went to the very best Public Schools,

You’ll never go wrong

with Everest Men,

So we select them again and again,

Again and again and again

and again.

You won't go wrong with Everest Men,

They went to the very best

Public Schools,

They play the game, they know the rules.

Listen to the “ Hamish MacInnes’s Mountain Patrol” song.

Gillies and shepherds

are shouting Bravo,

For Hamish Maclnnes, the Pride of Glencoe.

There'll be no

mercy mission no marathon slog,

Just lift your receiver and ask them for DOG.

They

come from their Kennels to answer the call,

Cool, calm and courageous the

Canine Patrol.

Sniffing the boulders and scratching the snow,

They've left

their mark on each crag in the Coe.

All sorts of characters are mirrored in the verses with an

economy that any writer would envy : Bill Murray of the 30’s, Chris Bonington

and Joe Brown of the 60’s, the stuffier members of the Cairngorm Club none with

wickedness for Tom was essentially a kindly man, however hard his exterior. For

example, I offended him once by writing an ill-chosen phrase which made it look

as if I numbered him among the vain-glorious whom I was criticising. He could

have satirised me and made me look a fool. He merely told me I was, but accepted

my explanation and we remained friends.

He was a son of the manse. But I never heard him talk about

God until our last day in Applecross. He opened his heart on many things as we

talked in the car. Tom had no conventional religion, but he believed that the

good in man lived on after he was dead, therefore there must be an all-seeing

God. We talked about the Himalaya, the Mustagh Tower, Rakaposhi, and the

Norwegian routes he had been making with Joe Brown. None of them shone for him

so much as his early days with his Aberdeen friends.

He did not think it was sentiment. In these early years all

of them were true mountain explorers, opening up new corners of Scotland for

the very first time. With the rapid sophistication of climbing and its

organisation in the ’60’s something simple and joyous had vanished. There was

too much emphasis on reputation, too much talk about character-building.

Freddy Malcolm and his friend “Sticker” are recalled in the

book. They were the leaders of a tiny group of working lads who called

themselves the Kincorth Club. As Tom says, they came to regard Beinn a’ Bhuird

as club property and built a subterranean “ Howff on its flank. I was proud to

be asked to be their hon. president. These boys had a quiet style, so quiet

that “night after night their torchlit safaris trod stealthily past the Laird’s

Very door, shouldering mighty beams of timber, sections of stove-piping and

sheets of corrugated iron. The Howff records the opening ceremony: 'This howff was constructed in the Year of Our

Lord I954, by the Kincorth Club, for the Kincorth Club. All climbers please

leave names, and location of intended climbs ; female climbers please leave

names, addresses and telephone numbers'.

No outdoor centres could turn out lads

like these.They developed their own characters and became First class performers in any Cairngorm climbing

situation, and most of their Winter pioneering of hard routes was done in the

remotest corries. They knew what they were doing. This is how Patey sums up his

companions of his Cairngorm days “The North-East climbers of the early ’50’s

were all individualists, but never rock fanatics. There are no crags in the

Cairngorms within easy reach of a motorable road and a typical climbing

week-end savoured more of an expedition than of acrobatics. If the weather

turned unfavourable, then a long hill walk took the place of the planned climb.

All the bothies were well patronised - Luibeg, Lochend, Gelder ,Shiel, Bynack,

the Geldie bothies, Altanour, Corrour and, of course, the Shelter Stone. At one

and all you would be assured of friendly company round the fire in the

evenings. Everybody knew everybody.”

But even the more halcyon days had their shadows as Tom

recounts, when in August I953 Bill Stewart fell to his death on Parallel Gully

B.’ Although his initial slip was a mere six feet, the rope sliced through on a

sharp flake of rock and he fell all the way to the corrie floor. It was a cruel

twist of fate to overtake such a brilliant young climber, and for many of the

‘faithful’ it soured the love of the hills they had shared with him.

“The majority of the old brigade took to hill Walking and

skiing where they could forget unhappy memories and still enjoy the camaraderie

of the hills.” But the impetus to make new routes, though by a smaller number

of climbers, went on, and rich harvests were reaped by the “ faithful.” But the

Aberdeen boys were no stay-at-homes. Patey’s men broke new ground in Applecross

and Skye, laying siege to Alpine peaks

of increasing difficulty season by season. Serving in the Royal Navy from 1957

to 1961, Tom was attached to Royal Marine Commando, thus had plenty of scope in

a unit practising mountain warfare at home and abroad. Marriage could not have

been very easy for his wife Betty, for a climbing genius is not the most

restful man to live with.

Just look at his record over the past half-dozen years, with

his assaults on Atlantic rock stacks and forays into every comer of the

North-West, including the first winter traverse of the Cuillin of Skye, with a

night out on the ridge. Then in 1970 he did what I think is probably the

boldest piece of solo climbing in the history of Scottish mountaineering by

crossing the great wall of Creag Meaghaidh, in 8500 feet of traversing in bold

situations “ unrivalled in Scottish winter climbing.”

I know of no one who thought it could be done in a single

day, yet Tom, starting around a normal lunch time, finished it in five hours in

conditions which were “ . . . far from ideal-an unusual amount of black ice and

heavy aprons of unstable wind-slab.” But

as he says in the book, it was one of these days when a climber is caught up in

his own impetus. One description made my stomach turn over in the sheer horror

of the situation. He had made a false move and was trying to rectify it when

the wind-slab ledge suddenly heeled off into space and I was left in the

position of a praying mantis, crampon points digging into verglassed slabs. It

was a moment of high drama-and horror best contemplated in retrospect. Hanging

on by one gloved fist jammed behind some frozen heather roots, I had to extract

a small ring spike from my pocket and batter it into the only visible crack. It

went in hesitantly for an inch and seemed to bite. Then the crack went blind.

Time was running out, as my supporting hand was rapidly losing sensation.” That

piton simply had to hold him, and it did, as he used his teeth and free hand to

thread the rope through it, then tested it by hanging free on it to try to

pendulum on to a lower ledge from where he might continue the traverse.

What a situation! Suspended on an inch of iron which might

or might not hold and certain death below if it failed. Even if it held he

still had a problem of achieving a landing on the ledge. “ If I missed it or

swung off backwards I would be spinning in space with little prospect of

regaining the cliff face. I arrived in a rush, sinking hands, knees and toes

simultaneously into a mound of powder snow.” He admits to teeth-chattering.”

The way now lay open. Perhaps you have dismissed Tom in your mind as a fool for

exposing himself to such extremes of danger and difficulty when he had a wife,

three children and the responsibilities of a scattered medical practice. Yet as

Christopher Brasher so well expressed it in his Foreword to the book: “What is

a man if he does not explore himself; if he does not challenge the impossible?”

I believe Tom Patey was a genius.

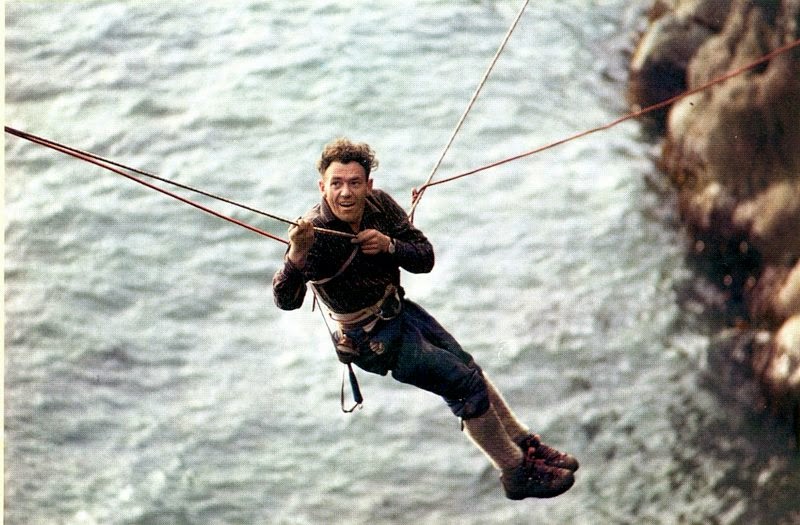

Joe Brown and Tom Patey on St Kilda

Tom Weir: 1972